Scientist Spotlight: Andrea Norton

Andrea “Andie” Norton is an ecologist studying the world’s changing rivers. She examines patterns in temperature and nutrients to assess the response of watersheds to climate change, and to build a record of how river environments are changing that could help flag current threats, predict future changes and develop strategies for successful management.

So what does that really look like? And who’s the person behind the data? We caught up with Andie to learn a bit more about the human behind Science on the Fly’s data and reports.

Q: What does a “day in the lab” look like for you?

Andie Norton: I'm currently at my office at Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Along with Science on the Fly (SOTF), I work with two other Woodwell projects; Cape Cod Rivers Observatory and Arctic Great Rivers Observatory. I run the analytical chemistry on water samples for all of them. Water samples for each project need to be analyzed for dissolved organic carbon, total dissolved nitrogen, ammonia, nitrate, ortho-phosphate, silica, and in some cases total phosphorus. All of that just entails a bunch of lab upkeep and mixing chemicals and maintaining the machines.

Q: What has you busy in the lab today?

AN: Today I was replacing a bunch of tubing on the Astoria, which is one of our primary water analysis instruments and it has a bunch of tubing connections because the chemical reactions happen within the tubing and the tubing affects the timing of the chemicals interacting. Unfortunately they have to be changed very frequently and it's exhausting. It's detached some of the skin from my thumbnail, from just trying to get tiny little tubes into other tubes. And then I was mixing a bunch of different chemicals, which can be time consuming because there are a lot of hazardous ones. You have to work under the fume hood wearing several layers of gloves and a lab coat and those chemicals have to be weighed precisely and cautiously. So you're just back and forth all day in the lab from chemical cabinets, to scales, to the fume hood and so forth.

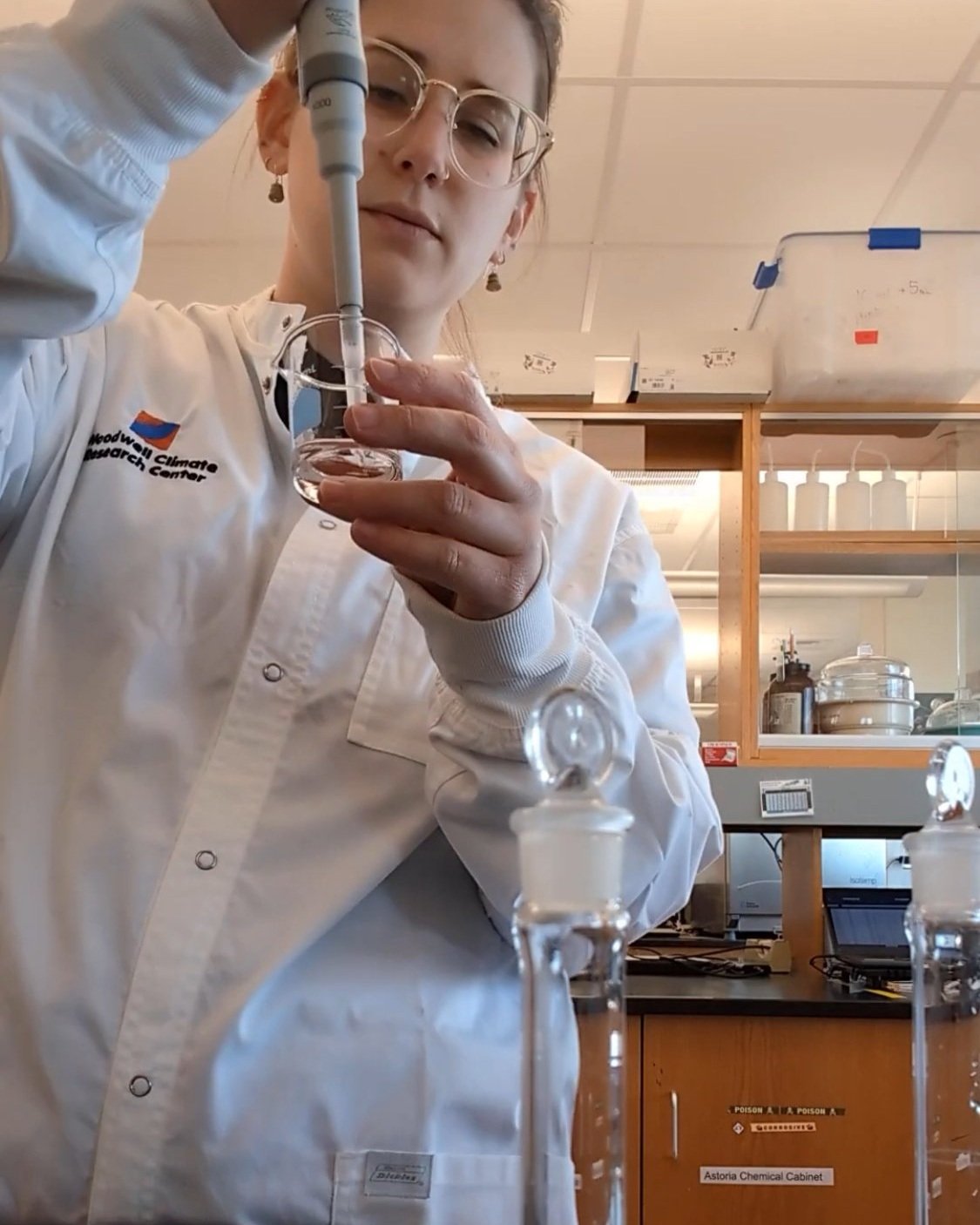

Andrea Norton working to analyze the water samples for the Science on the Fly project

Q: How did you make your way to Woodwell and Science on the Fly?

AN: I did my undergrad at Michigan Technological University, which is in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, surrounded by a lot of freshwater, it's surrounded in either direction by Lake Superior and just lots of small lake Superior Tributaries and streams. I really fell in love with small streams when I joined this freshwater biochemistry lab my sophomore year of college. They had me doing field work during the summer where I was knee deep in streams, running different incubations for nitrogen cycling and just doing a bunch of what I do now, but in the field. And meanwhile, I was learning to fly fish from my dad and always loved camping, always loved backpacking. I found this new love for water.

Q: Can you talk a little bit more about your connection to rivers?

AN: I think they're just so peaceful and soothing, and I always say I feel like every incredibly beautiful site on earth that strikes me is freshwater related, and more often than not, it's a river or a stream that's involved. There's just something about being near them and I take any opportunity I can to get my feet in them or swim in them or be next to them and take a nap—whatever it is.

Q: Is there a river that you connect with more than others?

AN: Probably the Sioux River up in northern Wisconsin. I grew up camping there and have really fond memories of that first connection with the outdoors. We would spend all day hiking up or down the river and all evenings sliding down this slippery rock, a big boulder in the river that was a little slide. It’s where I first fished and camped.

Q: You spent this time on the Sioux and playing in it, hiking alongside it, sliding into it, and now you spend a lot of your time in the lab looking at the details and uncovering the stories that rivers are working to tell us. What does that feel like for you?

AN: It's funny. I dunno, I feel like I know rivers on such a very microscopic level, but at the same time, I feel the lack of physical interaction often. Where I see a pattern in a river, but it can be hard to really put together the full story when I'm not just looking at the actual river. So it's often about finding new ways to understand a river when I’m not there in person. What is the history of this river? What's around it, what hasn't always been around it?

It’s also about experiencing rivers through other people's lenses. Allie and I've been working to set up interviews with each volunteer community scientist while I'm working on their report to hear what they see and what they know. People have really unique perspectives and knowledge and it really drives home to me that you can sit there and study something from afar for so long and know the chemistry intimately and know the processes intimately and the science, but it really doesn't matter if you don't have somebody or some context of the physical being there and seeing, feeling, smelling, touching.

Q: On the flipside, why is it important for people to understand the science and the data that you're finding in these rivers?

AN: I want to tie people to the process a little more. I think it's very easy when you don't fully understand the process to not have an appreciation for the amount of work that goes into it and what that one bottle really means. It's not as simple as I dump a little water in, push start and the machine spits out the answers. I have to be sure they filtered it well, that I've mixed everything just so, and that the machine is upkept and all these complicated processes are able to happen without interference to give these answers. Each nutrient is really different to analyze, so it's not the same process six times to get our six different constituents, each one is a unique process and takes time. I want to be able to tie people to that more so that they can feel like that the bottle has a big impact and that we put a lot of effort into the things they collect and what it really means. Not just” thanks, all done”. It's very involved and we treat it with a lot of care.

Q: Can you talk a little bit more about the connective tissue between SOTF’s community scientists and the impact of this work as a whole?

AN: You can really tell that every single community science scientist cares very much for their river, their sampling. You can tell that they care very much about the information they're able to provide to us. And then in turn, the information we're able to provide back, and I have to say every interaction and interview about a river has been productive. They all provide pieces of the puzzle that fit together. I might be the scientist, but I can't just come up with these answers on my own. We have these amazing community scientists who have so much knowledge at the ready, on the ground experience, and fantastic insight.

“It feels like I am not just doing science for scientists, I'm doing science for impact.”

Q: What's the value of empowering people on the ground? Community scientists, people who can walk out their back door and notice what's happening around them. What is the power in that, in your opinion?

AN: I think the biggest part is just that putting responsibility on people in that way makes them into advocates, stronger advocates. It's a whole conversation that is enlightening or leads to someone else going, “Wow, there's a stream in my backyard that I've never once thought about.” It’s putting that responsibility of stewardship more directly into people's hands. It creates this cascading effect of, hopefully, more people thinking about the world around them a little more. And the science side of things, It feels like I am not just doing science for scientists, I'm doing science for impact. I’m getting the information right back into people's hands. I feel like there's so much more impact behind everything I do, and that just, that's what keeps me going.

Q: Anything else you want to add?

AN: I hope everyone takes the time to appreciate that a lot goes into their samples and that it doesn't end when it leaves their hands and their mailbox. That’s just the beginning of the story. We spend a lot of time with it. I hope it invigorates everybody just to see the larger impact of what they're doing.

Oh, and I love when the community scientists ask me questions! I don't want them to ever feel like they can't reach out with questions like, “What might this cause or what might be the effect of this? Or why am I seeing this?” Never hesitate. I think questions are good, and it's good that we ask those because they might catch something that I missed. Questions are the foundation of science.